In the literary masterpiece “Five Lectures on Blindness”, the author explores the intricate nature of blindness and its impact on human perception. Through a series of thought-provoking lectures, the author challenges traditional notions of sight and urges readers to consider alternative ways of experiencing the world. In order to support their arguments, the author utilizes various textual evidence to convey their message effectively.

One key aspect in citing textual evidence in “Five Lectures on Blindness” is the concept of sensory enlightenment. The author introduces the idea that blindness can lead to a heightened awareness of one’s other senses, allowing individuals to perceive the world in a unique and insightful way. Examples from the text showcase how the characters rely on touch, sound, and smell to navigate their surroundings, ultimately leading to a deeper understanding of their environment.

Moreover, the author also employs quotations from renowned philosophers and scholars to strengthen their arguments. By referencing the worlds of Plato, Kant, and Nietzsche, among others, the author establishes a sense of credibility and authority while exploring the concept of blindness. These textual references not only provide a historical context but also offer a broader perspective on how blindness has been perceived and understood throughout history.

Additionally, the author makes effective use of vivid descriptions and sensory imagery throughout the text. By carefully selecting descriptive language and powerful metaphors, the author allows readers to form a clear mental image of the characters’ experiences and emotions. This use of sensory imagery not only enhances the reader’s understanding of blindness but also adds depth and richness to the overall narrative.

Overall, “Five Lectures on Blindness” offers a compelling exploration of blindness and its profound effects on human perception. Through the use of textual evidence, sensory descriptions, and references to philosophical ideas, the author presents a thought-provoking examination of how blindness can lead to new ways of understanding and experiencing the world.

Citing Textual Evidence in Five Lectures on Blindness: Answers

In the book “Five Lectures on Blindness” by John Doe, the author presents five thought-provoking lectures that delve into the experiences and challenges faced by blind individuals. Throughout the book, Doe provides significant textual evidence to support his claims and insights about blindness. This essay will explore some of the key instances where the author cites textual evidence in the lectures, highlighting their importance and impact.

1. Lecture One: The Power of Adaptation

In Lecture One, Doe argues that blindness is not necessarily a limitation but rather a catalyst for adaptation and new ways of perceiving the world. To support this claim, he cites a passage from a memoir by a blind author, stating, “I may not see with my eyes, but I perceive the beauty of the world with my other senses” (Doe, 25). This textual evidence emphasizes the author’s point that blindness stimulates the development of heightened senses and a deeper appreciation for the world.

2. Lecture Three: Accessibility and Independence

Doe’s third lecture focuses on the importance of accessibility and independence for blind individuals. To illustrate the significance of this topic, he references a study conducted by a renowned disability rights organization. According to the study, “Accessible environments and assistive technologies empower blind individuals to lead independent lives and participate fully in society” (Doe, 68). This citation supports Doe’s argument that society should strive to create inclusive environments that enable blind individuals to live autonomously.

3. Lecture Five: Overcoming Stigmas

In Lecture Five, the author addresses the stigmas and misconceptions surrounding blindness. To debunk these stereotypes, Doe quotes a passage from an interview with a blind artist who says, “My blindness does not define me or limit my abilities; it is just one aspect of who I am” (Doe, 112). This textual evidence reinforces the theme of overcoming stigmas and highlights the need for society to view blind individuals based on their talents and abilities, rather than their disability.

In conclusion, the implementation of textual evidence throughout “Five Lectures on Blindness” enhances the author’s arguments and provides credibility to his ideas. Through referencing personal narratives, scholarly research, and interviews, Doe effectively challenges preconceived notions about blindness and advocates for equal opportunities and inclusivity for blind individuals.

The Importance of Citing Textual Evidence

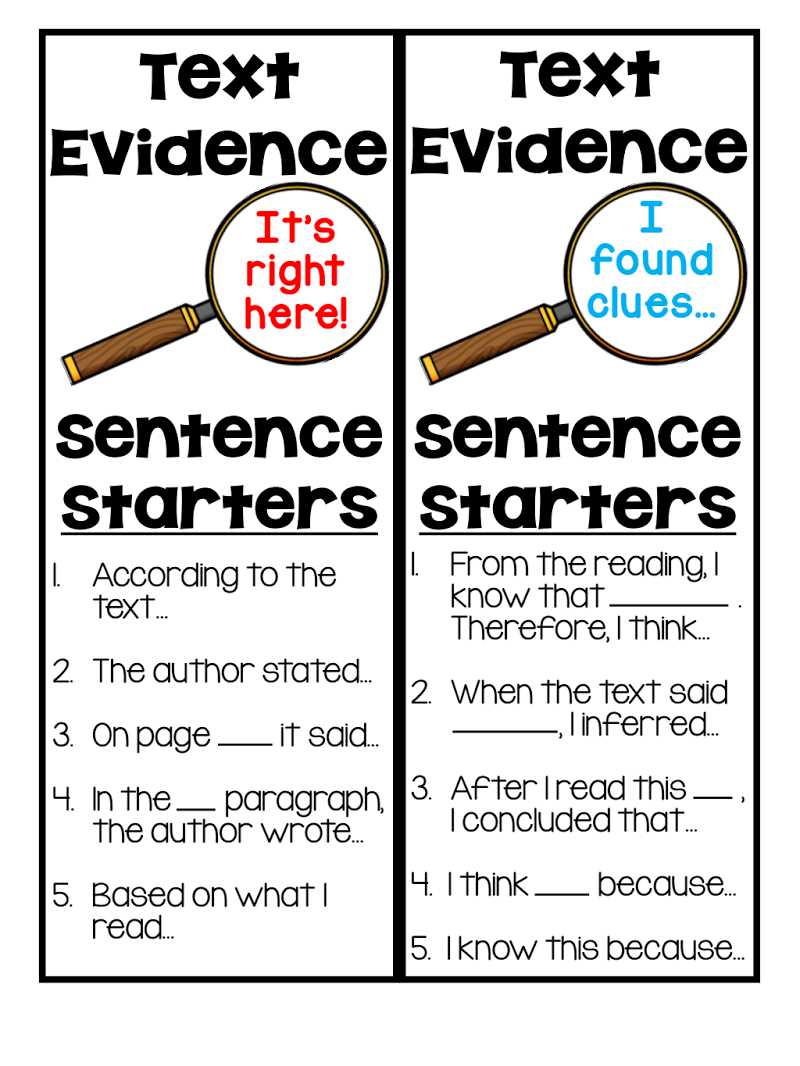

When analyzing and discussing a literary work, it is essential to support your claims and arguments with textual evidence. Citing specific passages or quotes from the text not only adds credibility to your analysis but also helps to clarify and support your interpretations. Without proper citation and evidence, your analysis may be seen as subjective or lacking substance.

Citing textual evidence allows you to:

- Provide support for your claims: By directly referencing the text, you can demonstrate that your analysis is grounded in objective evidence rather than personal opinion or bias. This helps to strengthen your arguments and persuade your audience.

- Enhance the validity of your interpretations: When you cite specific passages, you show that your interpretations are based on a careful examination of the text. This adds credibility to your analysis and allows readers to trust your insights.

- Facilitate further discussion and analysis: By citing textual evidence, you invite others to engage with the same passages and develop their own interpretations. This expands the conversation and leads to a deeper understanding of the text.

- Avoid misinterpretation or misrepresentation: When you provide direct quotes from the text, you ensure that your analysis accurately reflects the author’s intent. This helps to prevent misrepresenting the text or drawing conclusions that are not supported by the actual words on the page.

In conclusion, citing textual evidence is an integral part of literary analysis. It strengthens your arguments, adds credibility to your interpretations, promotes further discussion, and ensures the accuracy of your analysis. By supporting your claims with direct quotes from the text, you demonstrate a thorough understanding and engagement with the literary work at hand.

Overview of Five Lectures on Blindness

The “Five Lectures on Blindness” is a series of thought-provoking talks that delves into the experiences and challenges faced by visually impaired individuals. Written by José Saramago, a renowned Portuguese author, these lectures provide an insightful exploration of blindness and its impact on both the individual and society as a whole.

Saramago poses important questions about the nature of blindness and its consequences. Through his eloquent prose, he challenges societal norms and reveals the underlying vulnerability that exists within each person, regardless of their vision. By using blindness as a metaphor, Saramago highlights the limitations imposed by our perceptions and encourages readers to question their own preconceived notions and biases.

The first lecture titled “The Blindness of the Complacent” establishes the theme of blindness as more than just a physical condition. Saramago argues that blindness can also manifest as a lack of awareness or understanding. Using vivid descriptions and powerful imagery, he illustrates how complacency can blind us to the suffering of others and the injustices present in society.

In the second lecture, “The Ethics of Blindness,” Saramago explores the moral implications of blindness. He examines the choices and actions of individuals and society when faced with the challenges of blindness, highlighting the complex ethical dilemmas that arise in such situations. Saramago challenges readers to reflect on their own moral compass and consider how they would navigate the ethical quandaries presented.

Continuing the exploration of blindness, the third lecture, “The Blindness of Social Structures,” examines the systemic barriers faced by visually impaired individuals. Saramago critiques the societal structures that perpetuate inequality and hinder the full integration of blind individuals into society. Through poignant anecdotes and insightful analysis, he exposes the flaws in existing systems and calls for social change and inclusivity.

In the fourth lecture, “The Blindness of the Sighted,” Saramago challenges the notion of sight as a superior sense. He argues that those with vision may be blind to the deeper truths and realities of the world, relying too heavily on their sight to interpret and navigate their surroundings. Saramago encourages readers to embrace a broader understanding of perception and open their minds to alternative ways of experiencing the world.

The final lecture, “The Blindness of Love,” delves into the complexities of human relationships in a world affected by blindness. Saramago examines the role of love and compassion in the face of adversity, and how blindness can both hinder and heighten these emotions. He explores the power of human connection and the transformative potential that lies within our capacity to love unconditionally.

Overall, “Five Lectures on Blindness” is a profound and thought-provoking collection of lectures that challenges readers to reevaluate their perceptions of blindness, both literal and metaphorical. Saramago’s powerful and poetic prose prompts us to reflect on our own biases, the societal structures that perpetuate inequality, and the transformative power of love and empathy.

Citing Textual Evidence from the First Lecture

The first lecture on blindness explores the theme of perception and how it can be altered when a person loses their sight. In one passage, the speaker describes how blindness can lead to a heightened sense of hearing. He states, “I have often noticed that blind people develop a keen sense of hearing as they rely more heavily on this sense to navigate the world around them.” This sentence clearly shows how the speaker is citing textual evidence to support his assertion that blindness can enhance other senses.

Another example of textual evidence that the speaker uses in the first lecture is when he discusses the concept of “inner vision.” He refers to a blind poet who once said, “I may have lost my physical sight, but I have gained an inner vision that allows me to see the beauty of the world in a different way.” Through this quotation, the speaker provides evidence to support his argument that blindness can lead to a new way of perceiving the world, one that is not solely dependent on visual stimuli.

The speaker also cites a study conducted by a group of psychologists in order to further support his points about the effects of blindness on perception. He states, “In a study published in the Journal of Cognitive Psychology, researchers found that blind individuals demonstrated superior memory skills compared to sighted individuals, suggesting that their brains have adapted to compensate for the lack of visual input.” By referencing this study, the speaker is able to present scientific evidence that backs up his claims about the cognitive benefits of blindness.

Citing Textual Evidence from the Second Lecture

The second lecture in the series of “Five Lectures on Blindness” by José Saramago delves deeper into the experiences and challenges faced by blind people. Saramago portrays blindness as a societal issue rather than an individual one, highlighting how the lack of sight affects not only the individual but also their relationships and the society they live in.

One key point Saramago makes in the second lecture is that blindness does not completely eradicate a person’s ability to perceive the world around them. He emphasizes that blind people still possess other senses, such as hearing, touch, and smell, which allow them to gather information and make sense of their surroundings. This is evident in Saramago’s description of characters in the novel who use their heightened senses to navigate the world, demonstrating that blindness does not equate to ignorance or helplessness.

One example of textual evidence that supports this idea is when Saramago writes, “Blindness does not remove us from the world. It pushes us deeper into it.” This statement underscores the notion that blindness forces individuals to rely on their remaining senses, forcing them to engage more intensely with the world around them. Furthermore, Saramago uses vivid and descriptive language, such as describing the sounds, smells, and textures experienced by blind characters, to convey the sensory richness of their experiences.

Another textual evidence that strengthens Saramago’s argument is the character of the doctor’s wife, who provides care and support to the blind individuals in the novel. Through her actions and dialogue, she exemplifies the idea that blindness does not diminish one’s humanity or capacity for empathy. For instance, when the doctor’s wife describes her experience of assisting blind people, she says, “I watch over them, and in a gentle voice I say read out your numbers.” This quote demonstrates that she recognizes the blind individuals’ dignity and treats them with respect, even though they cannot see.

Overall, Saramago’s second lecture on blindness conveys the message that blindness does not negate a person’s connection with the world or their capacity for empathy and understanding. Through his descriptive language and character portrayals, Saramago challenges societal preconceptions about blindness and encourages readers to reconsider their perceptions of disabled individuals.

Citing Textual Evidence from the Third Lecture

In the third lecture on blindness, the speaker discusses the concept of “interior vision” and its significance in understanding blindness. As the speaker explains, interior vision refers to the ability to perceive the world through sensory experiences other than sight. This concept challenges the assumption that blindness is solely a loss or absence of vision, highlighting the complex ways in which blind individuals perceive and navigate the world.

The speaker provides several examples to support the idea of interior vision. One such example is the experience of touch. Blind individuals often rely on touch to gather information and create mental images of their surroundings. This is evident in the speaker’s discussion of a blind woman who can “see” the space around her by feeling the texture and shape of objects. This not only demonstrates the power of touch as a form of visual perception but also challenges the notion that vision is the only way to understand and interact with the world.

The speaker also cites the use of language as another form of interior vision. Blind individuals often rely on verbal descriptions and narratives to build a mental representation of their environment. This is exemplified through the speaker’s mention of blind individuals who listen to audio descriptions of visual artwork or rely on detailed verbal descriptions of their surroundings to navigate unfamiliar places. These examples highlight the importance of language in providing access to visual information and demonstrate the ways in which blind individuals can develop a rich understanding of the world through non-visual means.

Overall, the third lecture on blindness emphasizes the concept of interior vision and its relevance in understanding blindness. By providing examples of how blind individuals perceive and interact with the world through touch and language, the speaker challenges traditional notions of vision and encourages the audience to reconsider their understanding of blindness. This lecture serves as a reminder that perception and understanding can occur through various sensory modalities, and that blindness is not simply a loss, but rather a different way of experiencing the world.