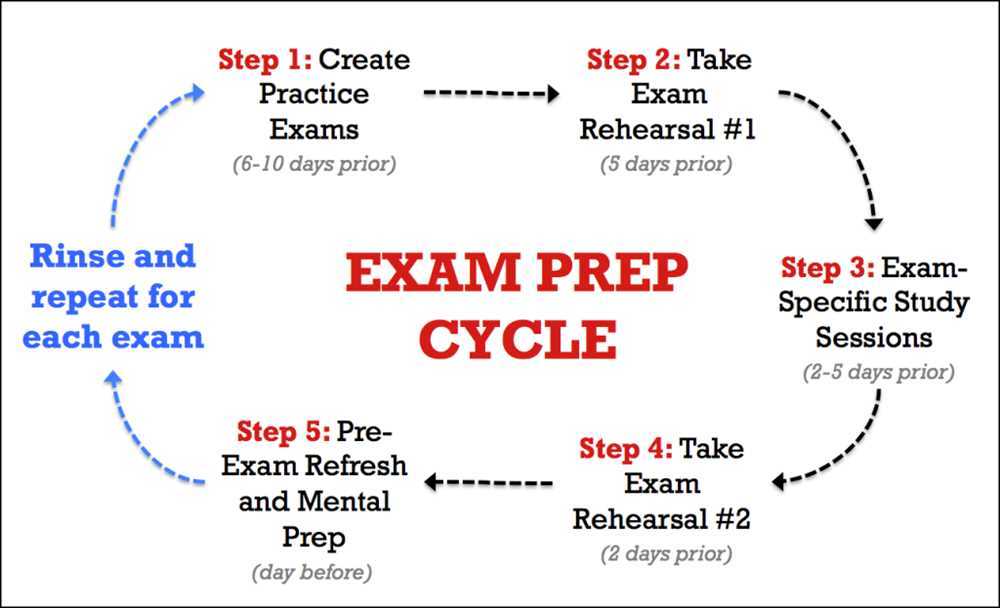

As the final exam in mechanics of materials approaches, it is essential to review the key concepts and topics covered throughout the course. This comprehensive review will help solidify your understanding of the subject and ensure that you are adequately prepared for the exam.

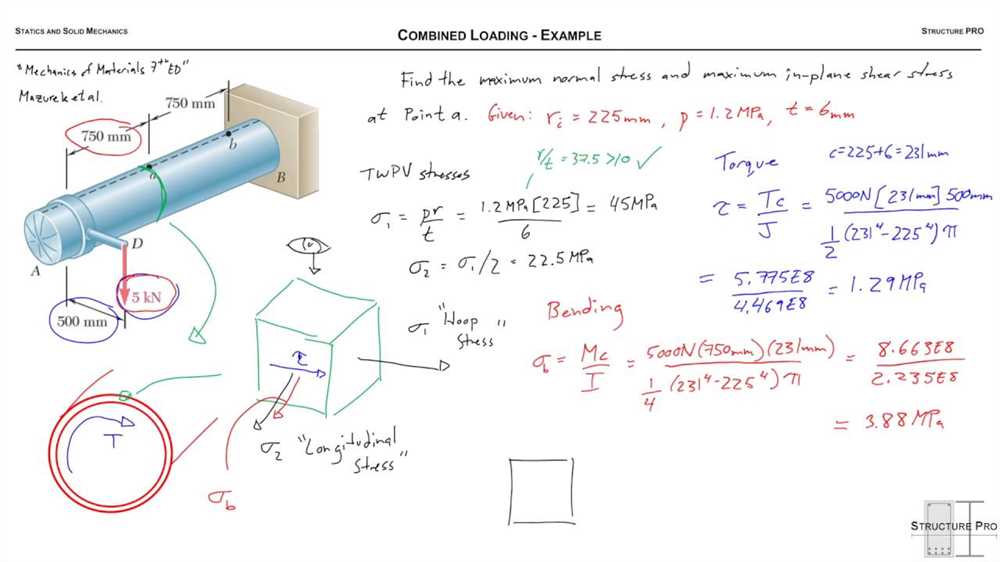

One of the fundamental principles in mechanics of materials is stress and strain analysis. This involves understanding how external forces and loads affect the internal behavior of materials. It is crucial to know how to calculate and analyze stresses and strains in different scenarios, such as axial loading, torsion, and bending.

Another important area to focus on is material properties and behavior. Understanding the mechanical properties of different materials, such as steel, aluminum, and concrete, will allow you to determine their suitability for specific applications. Additionally, learning about material failure criteria and how to predict the failure of structures is crucial for designing safe and efficient systems.

Furthermore, studying topics like beam deflection, column buckling, and energy methods will help you analyze and solve complex problems in mechanics of materials. Being able to apply the appropriate equations and formulas to determine the behavior and stability of structures is essential for real-world engineering applications.

In conclusion, reviewing stress and strain analysis, material properties and behavior, as well as beam deflection and stability concepts, will provide a solid foundation for your mechanics of materials final exam. By thoroughly understanding these topics and practicing problem-solving, you will be well-equipped to succeed in the exam and apply the principles of mechanics of materials to real engineering challenges.

Stress and Strain

In the field of mechanics of materials, stress and strain are fundamental concepts that describe the behavior of materials under external forces. Stress is defined as the internal resistance to deformation caused by the applied forces. It is calculated by dividing the force applied to a material by its cross-sectional area. The unit of stress is Pascal (Pa), which is equivalent to one Newton per square meter (N/m^2).

Strain, on the other hand, measures the change in shape or size of a material in response to a stress. It is calculated as the ratio of the change in length to the original length of the material. Strain has no unit, as it is a dimensionless quantity. Strain can be either tensile (elongation) or compressive (contraction), depending on the direction of the applied force and the resulting deformation of the material.

In engineering materials, stress and strain are related through a linear elastic behavior known as Hooke’s Law. Hooke’s Law states that the stress is directly proportional to the strain, within the elastic limit of the material. This means that as long as the applied stress does not exceed the elastic limit, the material will return to its original shape and size once the forces are removed.

Beyond the elastic limit, materials exhibit plastic deformation, where the stress and strain are no longer proportional. This is typically accompanied by permanent changes in the material’s shape or size. The point at which this transition occurs is known as the yield point.

In summary, stress and strain are key parameters that describe how materials respond to external forces. Understanding the relationship between stress and strain is crucial in predicting the behavior and performance of materials in various engineering applications.

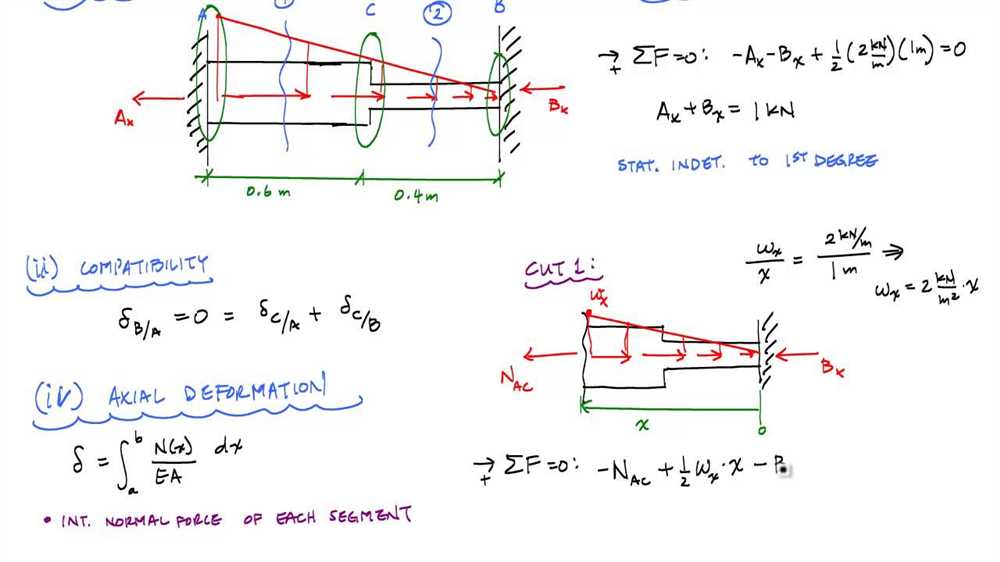

Axial Deformation

Axial deformation refers to the change in length of a structural member when subjected to an axial load. This type of deformation occurs when a force is applied along the axis of a member, causing it to either elongate or compress. Axial deformation is an important concept in mechanics of materials, as it allows engineers to analyze the behavior of materials and design structures that can withstand the expected loads.

The axial deformation of a member can be calculated using Hooke’s law, which states that the strain in a material is directly proportional to the applied stress. The equation for axial deformation is given by ΔL = (P * L) / (A * E), where ΔL is the change in length, P is the applied load, L is the original length of the member, A is the cross-sectional area, and E is the Young’s modulus of the material.

When a member is subjected to a tensile axial load, it elongates and experiences positive axial deformation. On the other hand, when a member is subjected to a compressive axial load, it shortens and experiences negative axial deformation. The magnitude of axial deformation is determined by the applied load and the characteristics of the material, such as its modulus of elasticity.

It is important for engineers to consider axial deformation when designing structures, as it can affect the overall stability and integrity of the system. Excessive axial deformation can lead to buckling or failure of the member, while insufficient deformation can result in overstressing and potential structural collapse. By understanding the principles of axial deformation, engineers can ensure that materials and structures are designed to safely accommodate the expected loads and prevent catastrophic failures.

Torsion

Torsion is a phenomenon that occurs when a bar or shaft is subjected to a twisting moment or torque. It is an important concept in mechanics of materials and plays a crucial role in the design and analysis of various engineering structures such as shafts, axles, and gears. Torsion primarily occurs when one end of a bar is fixed while the other is subjected to a twisting force.

Torsional Stress and Torsional Deformation: When a bar is subjected to torsion, it experiences a combination of shear stress and shear strain along its length. The shear stress is maximum at the outer surface of the bar and decreases towards the center. This distribution of stress results in torsional deformation, which is characterized by the twisting or rotation of the bar about its longitudinal axis.

Torsional Equation: The relationship between the applied torque, the geometric properties of the bar, and the resulting torsional stress and torsional deformation can be described by the torsional equation. This equation is derived from the fundamental principles of equilibrium and elasticity and allows engineers to calculate critical parameters such as maximum shear stress, shear strain, and angle of twist.

- Polar Moment of Inertia: The torsional resistance of a bar depends on its cross-sectional shape and size. The polar moment of inertia is a geometric property that measures a bar’s resistance to torsional deformation. It directly influences the maximum shear stress and angle of twist experienced by the bar.

- Shear Modulus: The shear modulus of a material indicates its resistance to shear deformation. It is an important parameter in torsion analysis as it relates the applied torque to the resulting shear stress. The shear modulus is a material property and varies for different materials.

- Torsional Failure: Excessive torsional stress can lead to the failure of a bar or shaft. The failure may occur in the form of shear cracking, yielding, or fracture. Designers and engineers must ensure that the maximum shear stress does not exceed the material’s allowable stress to prevent failure.

Torsion is a fundamental concept in mechanics of materials and its understanding is essential for engineers involved in the design and analysis of structures subjected to twisting forces. By considering factors such as torsional stress, torsional deformation, polar moment of inertia, shear modulus, and torsional failure, engineers can effectively design and optimize structures to withstand torsional loads.

Bending

Bending is a common phenomenon in mechanics of materials, especially when dealing with beams and other structural elements. It refers to the deformation of a material due to the application of a bending moment. When a beam is subjected to a bending moment, one side of the beam experiences tension while the other side experiences compression. This results in the beam bending, changing its shape and causing stress and strain within the material.

During bending, the material at the outermost fibers of the beam experiences the highest stress, known as the maximum bending stress. This stress is directly proportional to the bending moment and inversely proportional to the moment of inertia of the beam. The moment of inertia determines the beam’s resistance to bending and is based on the cross-sectional shape and size of the beam.

Bending can lead to various types of failure in a structural element, including elastic bending, plastic bending, and ultimate bending. In elastic bending, the material deforms elastically and returns to its original shape once the bending moment is removed. Plastic bending occurs when the material deforms beyond its elastic limit, resulting in permanent deformation. Ultimate bending refers to the point at which the material fails completely due to excessive bending stress.

Engineers often analyze bending in structural design to ensure that beams and other elements can safely withstand the expected loads and avoid failure. Understanding the principles of bending and the behavior of materials under bending is crucial for designing and constructing reliable and safe structures.

Shear Stress in Beams

In the study of mechanics of materials, shear stress in beams is a key concept that is often analyzed to determine the internal forces and deformations of structural members. Shear stress arises due to the application of transverse forces on a beam, which causes a parallel displacement of its layers. It is this displacement that creates shear stress within the beam.

Shear stress in beams can be calculated using the formula:

τ = VQ / It

Where τ is the shear stress, V is the shear force acting on the beam, Q is the first moment of area of the beam cross-section, I is the moment of inertia of the beam, and t is the thickness of the beam. This formula relates the shear stress to the applied shear force and the geometric properties of the beam.

| Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|

| τ | Shear stress in the beam |

| V | Shear force acting on the beam |

| Q | First moment of area of the beam cross-section |

| I | Moment of inertia of the beam |

| t | Thickness of the beam |

Understanding the shear stress in beams is crucial for designing and analyzing structural members. It helps determine the maximum allowable loads and ensures the integrity and safety of the structure. By calculating and analyzing the shear stress, engineers can assess the performance of a beam and make informed decisions to optimize its design.

Deflection of beams

The deflection of beams is an important concept in mechanics of materials. It refers to the displacement or bending of a beam under an applied load. Understanding the deflection of beams is crucial for designing structures that can withstand external forces and loads.

When a beam is subjected to external loads, it experiences internal stresses and strains. These stresses and strains cause the beam to deform, resulting in deflection. The amount of deflection depends on various factors, including the material properties of the beam, its geometry, and the magnitude and distribution of the applied loads. It is important to calculate and analyze the deflection of beams to ensure that they meet the design requirements and can safely support the desired loads.

The deflection of beams can be calculated using different methods, such as the integration method, the moment-area method, or by using numerical methods such as finite element analysis. These methods involve solving differential equations or using numerical techniques to determine the deflection at different points along the beam. The resulting deflection can be expressed as a linear or angular displacement, depending on the type of beam and the direction of the applied load.

In addition to calculating the deflection of beams, it is also important to consider the deflection limits specified by design codes and standards. These limits ensure that the deflection of a beam remains within acceptable tolerances to prevent excessive deformation or failure of the structure. The deflection limits typically depend on the type of structure, its intended use, and the material properties of the beam. By considering these factors and performing accurate deflection calculations, engineers can design beams that are both structurally sound and meet the performance requirements of the desired application.

Stability and Buckling

Stability and buckling are important concepts in mechanics of materials that deal with the behavior of structures under compressive loads. When a structure is subjected to compressive forces, it may deform and ultimately fail. The stability of the structure refers to its ability to resist these deformations and maintain its equilibrium.

One of the key factors that can affect the stability of a structure is its slenderness ratio. The slenderness ratio is defined as the ratio of the length of the structure to its smallest cross-sectional dimension. When the slenderness ratio is large, the structure becomes more susceptible to buckling. Buckling is a sudden and unstable lateral deformation that occurs when compressive forces exceed the critical buckling load of the structure.

To analyze the stability and buckling of structures, engineers often use the Euler buckling theory. According to this theory, the critical buckling load of a structure can be calculated by considering the material properties, geometric dimensions, and boundary conditions of the structure. By determining the critical buckling load, engineers can design structures that are stable and can safely resist compressive forces.

There are different types of buckling that can occur depending on the geometry and boundary conditions of the structure. Some common types of buckling include column buckling, plate buckling, and beam buckling. Each type of buckling has its own governing equations and conditions.

In conclusion, stability and buckling are important considerations in the design and analysis of structures. Understanding the behavior of structures under compressive forces can help engineers ensure the safety and reliability of their designs.